What the Lipschitz?!

Introduction

Lipschitzness of a function is essential for ensuring the convergence properties of many gradient descent algorithms

Definition

Simply put, Lipschitz functions are those which do not explode for some value \(x\). So, functions which change too fast and/or become infinitely steep are not Lipschitz functions.

More formally, let \(\chi \in \mathbb{R}^{d}\) be a d-dimensional subspace of real values. If we take a function \(f: \mathbb{R}^{d} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{n}\) which provides a mapping from a d-dimensional space to a p-dimensional space, we can say that \(f\) is \(L\)-Lipschitz over \(\chi\) if and only if we have:

\[|f(x_{2}) - f(x_{1})| \le L | x_{1} - x_{2} | \qquad \forall x_{1}, x_{2} \in \chi\]I always think this looks a bit confusing written this way, so a more intuitive way to write it is simply:

\[\frac{|f(x_{2}) - f(x_{1})|}{ | x_{1} - x_{2} | } \le L \qquad \forall x_{1}, x_{2} \in \chi\]where we now have the form of \(\Delta y / \Delta x\) on the left hand side.

Thinking about this a bit more, this condition demands that the slope of the secant line between two points \(x_{1}\) and \(x_{2}\) must be between \(-L \le m \le L\).

Example: Is cosine Lipschitz?

Start by employing the definition above,

\[\frac{f(x) - f(y)}{x - y} \simeq f^{'}(x) = \text{sin}(x)\]| We know that $$ | \text{sin}(x) | \le 1$$, so we can rewrite this as: |

where \(L = 1\). So we say that cosine is a \(1\)-Lipschitz function.

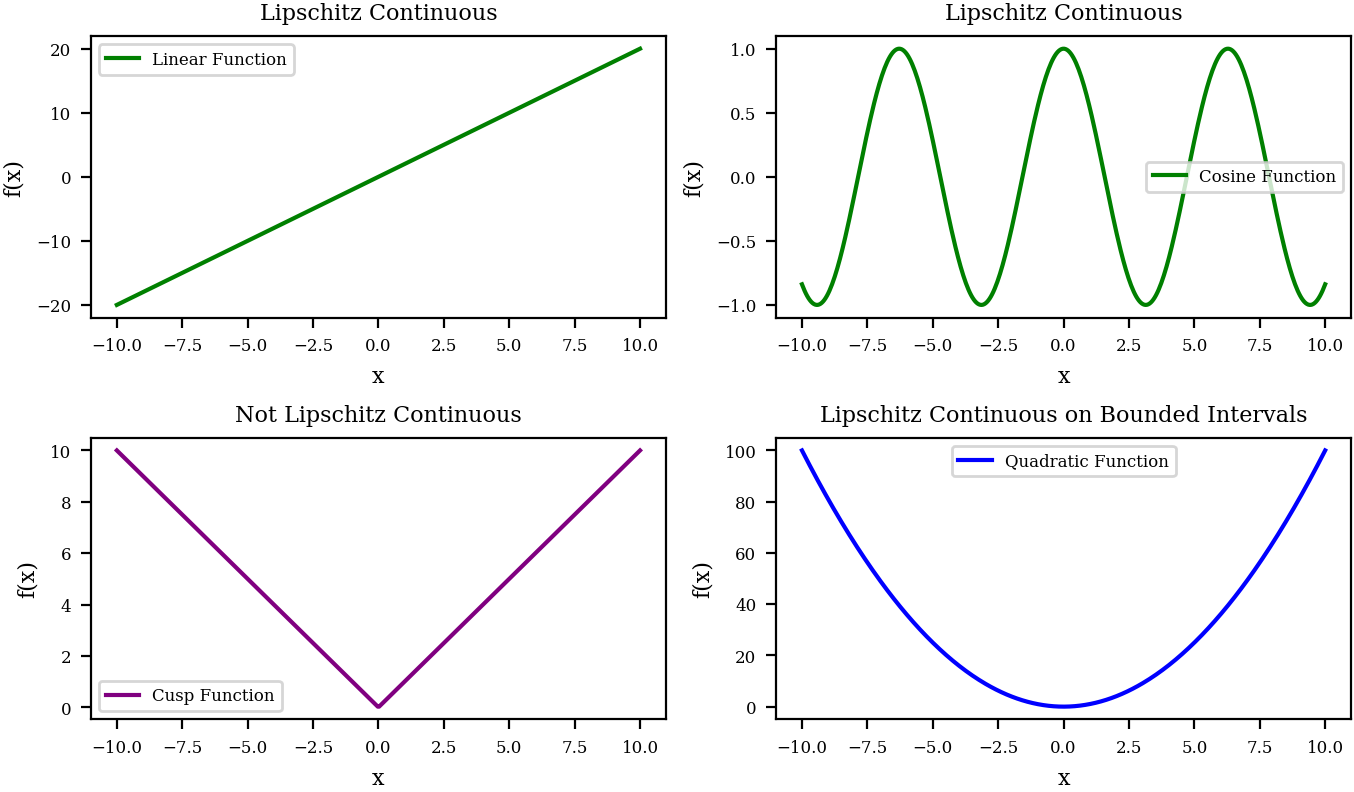

Now, if you’re screaming “Stop showing me maths!!”, you’re in luck, because I’ve created some nice plots for us to look at…

So, remembering our rule from above, we can see that the linear and cosine functions both satisfy the Lipschitz inquality as there is some bound on the slopes they exhibit for all \(x \in \chi\). On the other hand, the cusp function is not Lipschitz continuous at the origin because it has a discontinuity. Finally, the quadratic function is defined as Lipschitz continuous if and only if we are considering a bounded interval, because as \(x \rightarrow \infty\), the slope becomes arbitrarily large.

Globally & Locally Lipschitz

Just to round off this small post, I want to talk a bit about global and local Lipschitz functions. The above section kind of describes functions which are globally Lipschitz since we haven’t defined a subset of the function space to consider, so here, we’ll start local!

Say for example, we have some function \(f\) which is locally Lipschitz for a compact subset of \(\chi\). We’ll call this \(\Omega \subset \chi \in \mathbb{R}^{d}\).

For the local Lipschitz property to hold, it must be true that there is a constant \(L_{\Omega}\) such that,

\[|f(x) - f(y)| \le L_{\Omega} | x - y | \qquad \forall x_{1}, x_{2} \in \Omega\]where \(L_{\Omega}\) can indeed depend on the subset \(\Omega\). For example, the function \(f(x) = x^{2}\) has an \(L_{\Omega}\) which depends on \(x\) (since only one of the \(x^{2}\) will cancel). Therefore as the subset \(\Omega\) becomes larger, \(L_{\Omega}\) will scale linearly with this.

The above example defines a situation where we have local Lipschitzness but not global!

For global Lipschitzness, we require the function to have a Lipschitz constant which does not depend on the subset \(\Omega\), i.e. \(L_{\Omega} = L\).

Now, just looking back at our plot from earlier, we can observe that the linear and cosine functions are most definitely locally Lipschitz because they are globally Lipschitz continuous. But although the cusp and quadratic functions were not globally Lipschitz, they can indeed be locally Lipschitz. For example, the problem with the cusp function was just the point at the origin. So if we just ignore this point (define our compact subspace accordingly), we can find a Lipschitz constant. Then, for our quadratic function, we said that it needed to be a bounded interval before we could call it Lipschitz continuous. But the definition of local Lipschitzness is that the “local” is on a compact subspace which, you guessed it, is bounded! Thus a Lipschitz constant exists for any compact subset on the quadratics domain.

I hope this post has been a useful primer into the property of Lipschitzness. As always, feel free to reach out with any comments/questions!